Mutual fund dividends are one of the most common (and most misunderstood) parts of investing. Many people expect a mutual fund “dividend” to work exactly like a stock dividend—but mutual funds usually pay distributions, which can include stock dividends, bond interest, and even capital gains. Understanding how mutual fund dividends work helps you avoid surprises like a NAV drop after a payout, plan for taxes, and choose funds that match your income goals. In this guide, you’ll learn whether mutual funds pay dividends, how often they’re paid, and what they mean for your total return.

Do mutual funds pay dividends?

They can—and many do. But unlike a single company stock dividend (e.g., Coca-Cola paying quarterly cash dividends), a mutual fund’s payout depends on what happens inside the fund:

- The fund receives income (stock dividends, bond interest).

- The fund may realize gains by selling securities for more than it paid.

- By design (and often for tax reasons), the fund distributes much of that income/gain to investors.

In the U.S., many mutual funds are structured as Regulated Investment Companies (RICs), which generally must meet distribution requirements to maintain pass-through tax treatment. A key rule in U.S.Under tax regulations, a regulated investment company must usually distribute at least 90% of its taxable investment income (along with certain related amounts) as dividends in order to remain eligible for favorable tax treatment.

(Translation: funds commonly “push out” income to shareholders rather than pay corporate-level tax like a regular company.)

That said, not all mutual funds pay dividends in the way people expect:

- Some funds have very low income (e.g., growth-heavy equity funds that hold companies paying little/no dividends).

- Some funds may have no net gains in a given period.

- Some non-U.S. funds may follow different distribution norms and tax rules.

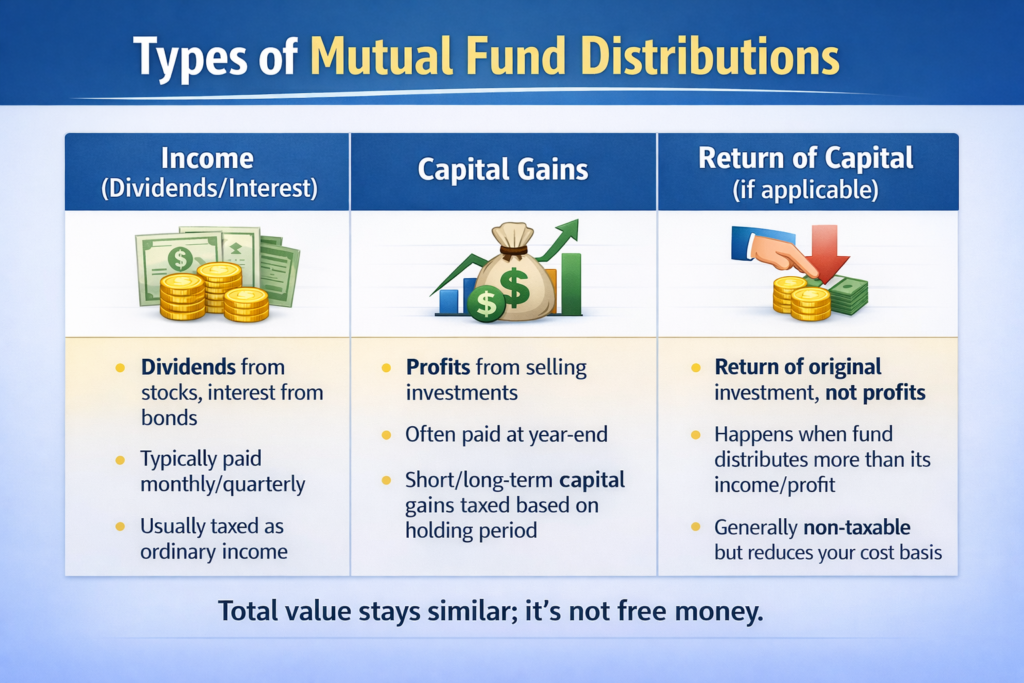

“Dividends” vs “distributions”: what you actually receive

When your mutual fund “pays a dividend,” you may be receiving one or more of these:

1) Income distributions (dividends + interest)

If the fund owns dividend-paying stocks and/or interest-paying bonds, the fund collects that cash and—after fees—can distribute it to shareholders. Fidelity notes that mutual funds that earn dividends and interest (or have net gains) are required by law to pass the largest possible portion of those earnings to shareholders.

2) Capital gains distributions

If the fund sells securities at a profit during the year, it may distribute those realized gains. This is one reason investors sometimes get a taxable distribution even if they didn’t sell any fund shares themselves—the selling happened inside the portfolio. T. Rowe Price highlights that mutual funds must distribute dividends and net realized capital gains earned over the prior 12 months, and in taxable accounts those distributions can be taxable even if reinvested.

3) Special categories (U.S. examples)

Some distributions may be categorized differently for tax purposes (e.g., qualified dividends, exempt-interest dividends). IRS guidance for investors (Publication 550) covers how mutual fund distributions can be treated for tax reporting.

How often do mutual funds pay dividends?

There’s no single schedule. Common patterns include:

- Monthly (often bond funds and money market funds)

- Quarterly (common for many stock index funds)

- Annually (often for capital gains distributions, especially year-end)

Real-world, current example: Vanguard publishes distribution calendars and year-end distribution tables. Vanguard’s “year-end distributions” listing shows many funds with December 2025 distribution activity and dates/amounts (income and capital gains) across hundreds of funds.

Vanguard also provides a 2025 dividend schedule PDF noting that some funds distribute dividends daily and then pay them monthly.

So: a mutual fund may pay “dividends” monthly, quarterly, annually, or irregularly, depending on the strategy and what income/gains occur inside the fund.

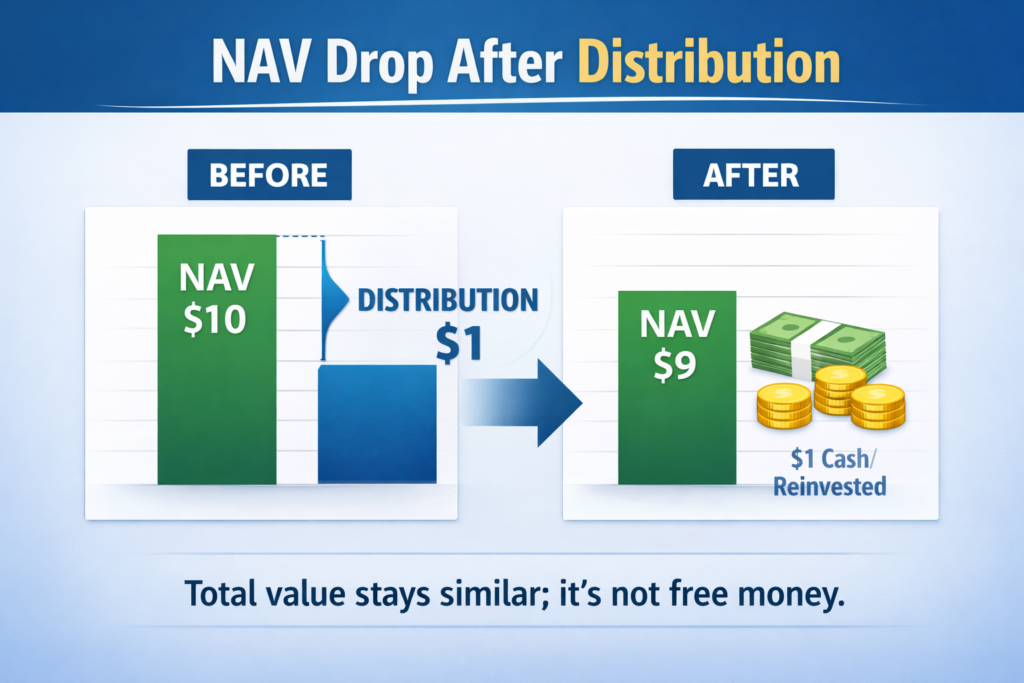

Why your fund price can drop right after a “dividend”

A common investor surprise is:

“My fund paid a dividend, but my account value didn’t go up—or it even went down!”

This is usually normal because on the distribution date the fund’s net asset value (NAV) typically falls by roughly the amount distributed. Think of it like taking cash out of the fund and handing it to shareholders.

J.P. Morgan Asset Management explains that a fund’s NAV per share decreases when income and gains are distributed to shareholders, and when capital gains are distributed the NAV reflects that amount (plus any market movement).

Example (simple math)

- You own 100 shares at $10 NAV = $1,000

- The fund distributes $1 per share

- NAV may drop to about $9

- You receive $100 cash (or $100 reinvested into more shares)

Your total value is still about $1,000 (ignoring market moves). The “dividend” isn’t free money—it’s a transfer from NAV to you.

Key performance tip: focus on total return (NAV change + distributions), not just NAV movement.

How you receive mutual fund dividends: cash vs reinvestment

Most brokers give you two main options:

- Take distributions in cash

The cash lands in your brokerage cash balance/bank sweep. - Automatically reinvest distributions

The distribution buys additional shares of the same mutual fund at the post-distribution NAV.

Reinvesting is common for long-term investors because it compounds returns (though it doesn’t avoid taxes in taxable accounts—more on that below).

Taxes: are mutual fund dividends taxable?

This depends heavily on your country and account type. Here’s a clear, generally useful framework:

In taxable accounts (U.S. overview)

- Ordinary dividends are generally taxable.

- Qualified dividends may be taxed at preferential rates if requirements are met.

- Capital gains distributions are generally taxable (short-term vs long-term treatment depends on how the gain is characterized).

- Reinvested distributions are still typically taxable—because you received the distribution; you just used it immediately to buy more shares.

The IRS explicitly covers mutual fund distributions and their treatment for individual shareholders in Publication 550.

And T. Rowe Price emphasizes the practical reality: in taxable accounts, mutual fund distributions can create taxes even if reinvested and even if the investor did not sell shares.

In tax-advantaged accounts (U.S. examples: IRA/401(k))

Distributions often don’t create immediate taxes inside the account; taxation is usually tied to withdrawals under that account’s rules. (Exact handling varies by account type and jurisdiction.)

Outside the U.S.

Many countries tax funds differently (e.g., withholding taxes, “distributing” vs “accumulating” share classes, deemed distributions, etc.). If you tell me your country and whether you’re investing via a local mutual fund or a U.S. fund, I can tailor the tax section to your rules.

How to check if a mutual fund pays dividends (and how much)

Use a simple checklist:

- Look at the fund’s “Distributions” page on the provider site

Fidelity and Vanguard both publish distribution histories and recent distribution amounts/dates. - Check the prospectus / summary prospectus

This tells you the fund’s distribution policy (monthly/quarterly/annual) and what types of income it expects to distribute. - Search for “distribution schedule” or “distribution calendar”

Some firms publish year calendars (Vanguard does for 2025). - Know what you own

- Bond funds / money market funds: often distribute more regular income

- Dividend equity funds: aim for higher dividend income

- Growth equity funds: may have lower distributions

- Active funds with turnover: may generate more capital gains distributions than low-turnover index funds (not always, but often)

- Bond funds / money market funds: often distribute more regular income

Practical tips to avoid “surprise” distributions

- Be careful buying right before a big year-end distribution

If you buy just before the distribution, you can get a taxable payout soon after—without having benefited from the fund’s rise that produced the gain (because the price adjusts downward). - Use tax-advantaged accounts when appropriate

This can reduce the pain of annual taxable distributions (jurisdiction/account rules apply). - Compare funds on after-tax returns and turnover

Lower turnover strategies often realize fewer capital gains (again: not guaranteed, but a useful lens). - Remember: distributions aren’t extra return by themselves

They’re one way your total return is delivered (cash vs NAV appreciation). J.P. Morgan’s explanation of NAV decreasing when distributing income/gains is a helpful mental model.

Bottom line

- Yes, mutual funds can pay dividends, but the more accurate term is distributions (income + realized gains).

- Frequency varies (monthly/quarterly/annual), and providers publish current schedules and histories (Vanguard and Fidelity are good examples).

- NAV typically drops when a distribution is paid, so judge performance by total return, not just the payout.

- Tax treatment depends on jurisdiction and account type, but in U.S. taxable accounts, distributions can be taxable even if reinvested.

If you tell me your country and whether you’re investing through a taxable brokerage vs retirement/pension account, I can tailor the tax part and give a “what to expect” distribution schedule by fund type (equity/bond/money market/index/active).